Pyrolysis, Perfectionism, and Other Projects

At the beginning of May, Michael moved into my parents’ basement—I followed him from Houston two weeks later. We lived there for two months, while all our stuff (besides two suitcases of clothes and Keana the cat) was barricaded into a 25-foot-deep storage unit behind a wall of precariously stacked lawn furniture. [The only thing that broke in our move: one cast-iron patio chair. How? I’m still wondering.] Those months at my parents’ house provided a liminal landing place, a spot from which we could get our bearings and ease into being Boulderites. I pulled my little black particle-board desk out of the storage unit and spent those two months drafting essays on the back deck, gazing out over my dad’s rose gardens. Michael spent those two months resisting the urge to start any new projects.

“Even though the wasteland would be ideal for pyrolysis,” he pointed out. ‘The wasteland’ refers to the unfairly nicknamed back .40 acres of my parents’ yard, and pyrolysis refers to the process of heating things—typically to the point of combustion—in the absence of oxygen. As one does.

“Michael, please don’t be responsible for this summer’s wildfires,” I requested. Every Colorado kid knows that every summer the entire state just bursts into flames. And every Colorado kid also knows you don’t want the overworked firefighters to trace the source of those flames back to you: a cigarette dropped in a national forest, a campfire only partially peed on that stayed smoldering through the night, a gender reveal party gone awry. Or any backyard combustion attempts.

“Okay, I promise not to light the state on fire,” he begrudgingly replied. We made it through wildfire season and Michael has, true to his word, not started a single blaze. He looked into pyrolysis—even had a few phone calls with a former energy economics professor about it—and then decided to try some different projects.

We got into our own house at the beginning of July. My second semester of grad school started, so I started drafting essays to turn into my new advisor every Sunday night. Michael got back to project-ing. At first, his projects were immediate and practical, focused on the house and getting us settled. Every weekend took on its own objective: one Saturday, he programmed and installed a new custom watering system for the garden. The next Saturday, he used a jug of viscous mineral oil to seal and polish two massive, butcher-block cutting boards his mom had snapped up for us at a garage sale.

One week, Michael went to play pickle ball with some retirees he connected with on NextDoor. He came home with a backseat full of hops: tangled spools of sticky, velcro-barbed vines dangling with acorn-sized chartreuse ornaments. We strung them around the back porch and I spent that week’s leisure hours delicately separating hop from stem so we could spend that Saturday home-brewing our first batch of beer. We boiled the hops so efficiently that when Michael attempted to weigh a sample of the sugary, pre-fermentation sludge, the math suggested we would end up with a ferociously boozy and bitter triple IPA. We strained and funneled and bottled the stuff, left it to ferment underneath a moving blanket in the utility sink in the basement, and when we popped our first bottle open, it tasted like beer! We toasted to our house, our successful home-brew experiment, and vowed to keep trying new things.

Michael decided if we could make our own beer, we could make our own wine, and he started researching how to get grapevines. Before getting vines, though, Michael decided he would need a place for them in the yard. When Michael’s friend Matt visited, Michael capitalized on the availability of an additional laborer and the two of them spent a day clearing a portion of the backyard hill for our forthcoming vineyard. Matt laid a series of boards to create a tasteful entrance to the vineyard and they lined the soil plot with smooth stones. After further research, Michael learned that the best time to purchase grapevines is in January, so for the past few months, Keana the cat has relished having her own expansive, very posh dirt bath.

[To the right: tiny cat, large dirt plot. Vineyard pending.]

Michael ordered a 3D printer and, within 24 hours of its arrival, started printing ashtrays.

“We’re not smokers,” I pointed out. He was undeterred. “I have to make a model, to make a mold, so I can cast them out of metal,” he explained. In the following days, we received a slough of Amazon packages. I checked our purchase history to figure out what they were: a ceramic casting cup, a heating element, and a furnace crucible.

“I’m building a forge,” he said. “Well, I’m not exactly building a forge.”

“So you’re building a forgery,” I said. He rolled his eyes.

Colorado’s emphasis on reuse and minimizing waste has resulted in a bounty of creative recycling centers. My mom introduced Michael to a place called EcoCycle, a public-facing arm of the local waste management utility. EcoCycle operates out of a loosely categorized scrapyard on the edge of town where you can buy anything from gently used building materials to vintage washing machines to old buckets, all deeply discounted. Inventory changes pretty quickly—those castoff sink pedestals just fly off the ramshackle racks—so Michael decided to start stopping by in regular intervals so he wouldn’t miss anything good. He was looking for a metal container in which to build the forgery, but first, he spent $25 on an antique table saw.

The saw was extremely rusted when he brought it home (but a little rust is no challenge for Michael “Mad Scientist” Watson-Fore!). He looked it up and found that it was a 1950s model, originally purchased from the Sears & Roebuck catalogue. It was a little banged up: lead stuck in the gears, the axle-turning bolt was completely stripped, and it hadn’t been cleaned since it was first mounted. Michael disassembled the entire thing in order to clean it, and in doing so discovered that the previous owner had attempted several unsuccessful fixes. Michael disappeared into the garage with his new, pointy toy and emerged victorious several days later.

“I’ve restored it,” he announced. (In the days following this restoration, I heard him marvel about the different approach to safety protocols back in the 1950s. Evidently, this restored table saw is now the most dangerous thing we own. Cool.)

Around this time, Michael started perusing the Colorado Public Surplus website: an auction site used to sell off unwanted government property—stuff from schools, municipalities, airports, post offices… Most items are fairly unsurprising: cheap cars, old computer parts, electronics. Michael was tickled to find an auction listing for a sheep.(Since it was being sold on Public Surplus, that sheep must’ve been a former government operative, or used for experimental testing. I imagine.) Michael forwarded the listing to our landlady to gauge her response. (She didn’t respond.) Later, he told her he’d sent the listing by accident.

“Sheep happens,” she replied.

Michael made his first purchase from Colorado’s Public Surplus a few days after that, which I learned about not because he told me but because I saw a picture of his haul on social media while I was on my break at work. He’d posted a snapshot of a spectrometer buckled into the backseat of his Camry. “2 for $200!” he captioned it.

“This place is a scavenger’s playground,” Michael said one morning. I looked at him quizzically. Other than the two bears that deposited a neon-orange heap of scat in our backyard a month ago, or the burly raccoons that leer at me when I’m biking home from work, I haven’t noticed many animals looking for food. Over his shoulder I noticed that Michael was scrolling the Free section of NextDoor. By ‘scavengers’ he didn’t mean raccoons; he meant himself.

[Right: Michael removing the power supply from a microwave we picked up out of somebody’s driveway during a morning coffee run. It had been posted on NextDoor for free, he said.]

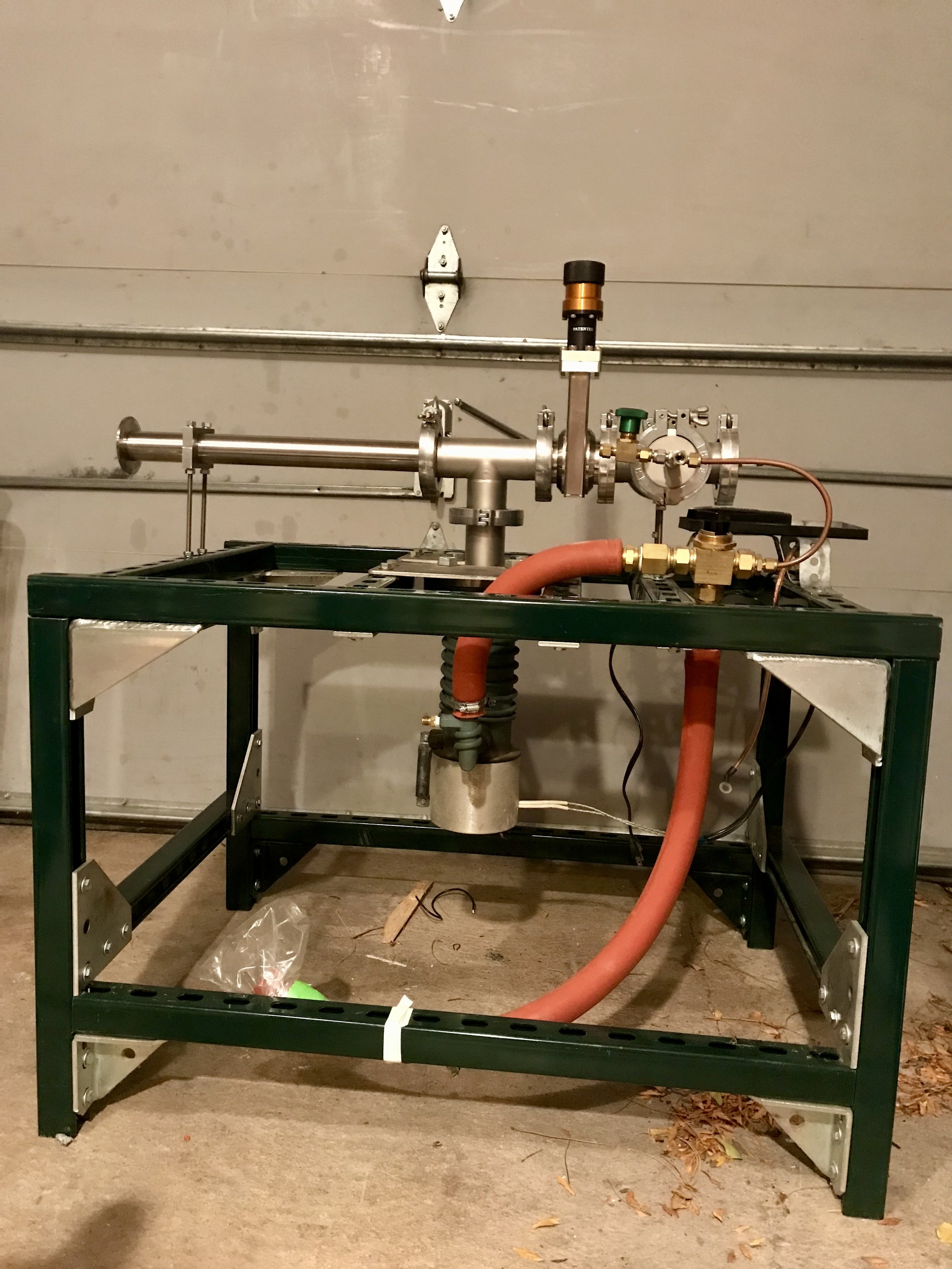

That weekend, we rearranged our Sunday plans to borrow my dad’s truck and go pick up a vacuum chamber.

“We already have a vacuum,” I pointed out. Michael explained that it wasn’t a suck-up-dirt kind of vacuum; it was a create-an-airless-environment-for-SCIENCE kind of vacuum. Of course. Silly me.

The vacuum turned out to be a massive, four foot long stainless steel ray gun-looking thing, discreetly covered in plastic and waiting for us in the garage of a nondescript suburban house near the local mall. The man who was giving it away had built it himself, back in ’93, and was thrilled to find someone who might be able to use it. He spoke enthusiastically, telling Michael how to use the pump, how to install a cooling system, how to manage the transition from low vacuum to high vacuum. I stood off to the side, my eyes glazing over, trying to pretend like anything he said held any meaning for me.

“This thing can go down to ten to the minus eighth!” the man said. I don’t know what that means, but it sure sounds impressive. I think.

When the man finished grilling Michael about his intentions (the whole scene felt oddly reminiscent of a father interviewing his daughter’s date: “Tell me about the nature of your interest in my daughter/vacuum chamber”), we hoisted it into the back of the truck and covered it with a blanket. That was the only way to keep it from looking like we were going to atom-blast whatever car got in the lane behind us.

[“If the FBI come for us, they’re going to use this as evidence,” Michael says. Atom blaster to the right.]

All this scavenging is building towards something (I hope), though I could hardly tell you what. The other night, I was sitting in my armchair editing essays when Michael burst through the back door. His interruption came at an opportune moment, since I was slumped over, disappointed with what felt like another clunky draft, going nowhere.

“McKenzie,” he said. “Wanna come see what I’m doing in the garage?”

I hopped up from my child-sized velvet armchair ($10 out of somebody’s garage, baby; maybe this place is a scavenger’s paradise) and followed him out the back door in my pink fuzzy socks. Shoes definitely would have been more appropriate, but I didn’t know what he was about to show me.

The red, dorm-fridge-sized metal locker he’d found at EcoCycle was hooked up to enough electronics for a resuscitation scene in Gray’s Anatomy. (I practically expected Michael to shout, “CLEAR!” in order to get the thing running.) Water pumped from a Tupperware basin as a cooling function to keep the wrong parts from melting. Copper tubing poked out of side of the red container, encircling one of the ceramic casting cups he’d bought online. The whole contraption looked like an elaborate amusement park for ants.

“Stand back, but look in,” Michael instructed. He gestured towards the crucible and used grill tongs to remove a square-inch piece of concrete that covered the cup’s opening. I craned my neck to see inside. A mysterious substance glittered brightly in the bottom of the cup. “Molten copper,” he said. He picked up another twist of copper wire in his tongs and pushed it into the cup before replacing the concrete shard lid.

Michael worked continuously, monitoring an electronic screen and adding more copper every couple seconds. One of the copper twists was too long to fit in the cup with the lid on, so he set down his tongs and grabbed the blowtorch, smelting the wire twist from above even as it heat from the forgery softened its solid form. Copper salts burned off in noxious-looking, green puffs.

“In a minute, I’m going to pour it into the mold in the casting sand behind you,” Michael informed me. I glanced at the readout on the small electronic screen. Digital numerals representing voltage, amps, and kilowatt hours flickered against the dull gray backdrop. One of the figures was declining, like a kite that lost its wind and was tumbling back to the earth. “The problem is, the hotter it gets [inside the furnace], the less effective [the power supply] is, so there’s a sweet spot, and I’m not quite there,” Michael said. “I don’t have enough copper melted, but I need to pour now.” I leapt out of the way, skittering like a deer to the other side of the garage, since I had no interest in acquiring any dramatic molten-copper-burns. He moved steadily, picking up the ceramic cup with a non-conductive implement, and pouring the lava-like metal into the mold. The copper, away from the heating element, pooled on top of the mold and solidified almost immediately. The pour was a failure.

Rather, the pour was an attempt, an iterative stage in an ongoing process. Where I assume failure, Michael sees development.

“That time didn’t work, but I know exactly what to do next time,” he told me. For Michael, everything seems to be process. No setback is final. As long as he doesn’t die in a tragic explosion, no version of his experiments has to be considered final. The joy is in the discovery, not the accomplishment.

Michael flicked off the power supply to the forgery, and we turned off the lights in the garage. I went back inside, dusted a few clingy leaves off my fuzzy socks, and folded myself back into my child-sized armchair. The draft that had been frustrating me half an hour before still glowed hauntingly on my computer screen. I nudged the cursor and got back to work.

So he’s still smelting and scavenging and spectrometing. And I’m writing and editing, and practicing patience and self-compassion.